UWorld Qbanks Step 3 Updated 04/2020 (System Wise & Random Wise) 2. OnlineMedEd WhiteBoard Snapshot for Clinical 2020. OnlineMedEd for Clinical 2020 (USMLE STEP 2) (Updated 07/2020) 4. KAPLAN On Demand USMLE Step 3 2018. Doctor In Training Step 3 2020. Doctor In Training Step 3 2018. DIT Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine Review 2019. USMLE® Step 1; USMLE® Step 2 CK; USMLE® Step 2 CS; USMLE® Step 3. The number of questions shown here is for informational purposes only and is subject to. Download UWorld for USMLE Step 1 2018 Free Download USMLE UWorld Step 1 PDF Free Alright, now in this part of the article, you will be able to access the free PDF download of UWorld Qbanks 2019 PDF using our direct links mentioned at the end of this article. USMLE STEP 3 QBANK Overview With years of experience, Archer has provided the best lectures and question banks to prepare for medical licensing exams. These Lectures as well as USMLE step3 Qbank questions and answers will help you not just to score high on Step 3 but also help you become a better clinician.

UWorld Step 1 Qbank 2020 Free Download

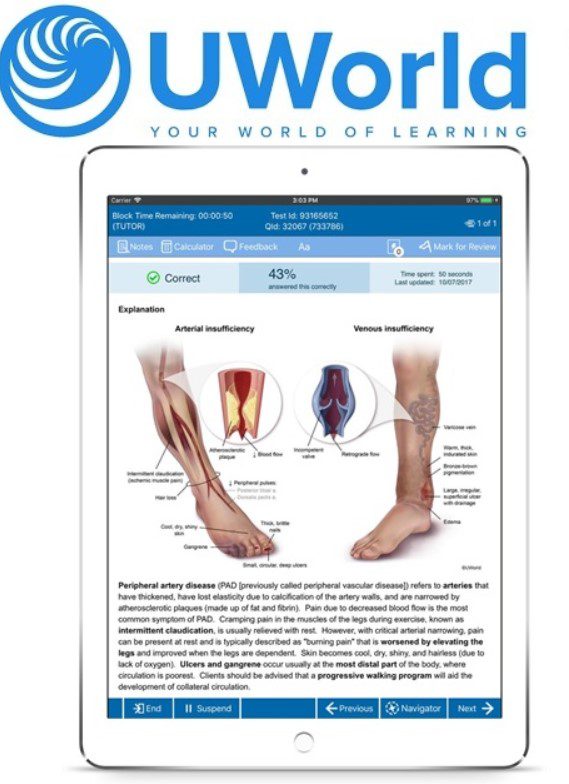

Since 2001, nearly all medical students in the United States have trusted UWorld to prepare for their licensing exams. Being at the forefront of medical education gives us an obligation to provide students with only the best practice questions and explanations. Our goal is not only to prepare you for the USMLE, but to help you become a better clinician.

Key Features

3,000+ challenging Step 1 questions

Real-life clinical scenarios test high-yield basic science concepts

Content created by practicing physicians with extensive experience

Continuous updates to maintain high standards of excellence

In-depth explanations

Conceptual focus on important preclinical and clinical topics

Detailed explanations for incorrect options

Vivid illustrations to help master the content

Performance and improvement tracking

Exam-like software interface

Highlighting of relative strengths and weaknesses

Performance gauging with peer-to-peer comparison

SociaDrive Part 1|SociaDrive Part 2|SociaDrive Part 3

Step 1

If you have questions or issues, check out the Frequently Asked Questions: Practice Materials. If you do not find the answer you need, please fill out our contact form.

USMLE Computer-based Testing (CBT) Practice Session

Practice Sessions are available, for a fee, for registered examinees who want the opportunity to become familiar with the Prometric test center environment. Register for a CBT Practice Session »

Step 2 Clinical Knowledge (CK)

Practice materials updated August 2020

Please view the announcement regarding upcoming Step 2 CK content changes.

If you have questions or issues, check out the Frequently Asked Questions: Practice Materials. If you do not find the answer you need, please fill out our contact form.

USMLE Computer-based Testing (CBT) Practice Session

Practice Sessions are available, for a fee, for registered examinees who want the opportunity to become familiar with the Prometric test center environment. Register for a CBT Practice Session »

Step 2 Clinical Skills (CS)

USMLE Step 2 CS is Temporarily Suspended

- Testing at CSEC centers for Step 2 Clinical Skills (CS) is currently suspended. All Step 2 CS results from exam administrations prior to the suspension (March 2020) will be reported on USMLE transcripts. Due to the Step 2 CS suspension, a significant number of individuals applying for residency in the 2020-2021 cycle will not have a Step 2 CS result or an opportunity to retest after a Step 2 CS failure. Information on the timing of this suspension will be clearly communicated to residency programs through ERAS. While Step 2 CS is suspended, the ECFMG has posted requirements for Certification for the 2021 residency Match, available here.

- The USMLE program is also working with the medical education and regulation community to mitigate the impact of this testing disruption.

- Listen to a podcast for insights into the decision making process, alternative delivery options that were explored, and next steps for the USMLE program to consider. (June 10, 2020)

- Read an announcement about the continued suspension of Step 2 CS to determine the optimal approach to clinical skills assessment without compromising the health and safety of examinees and test center staff.(May 26, 2020)

Practice materials updated September 2019

- Video examples of examinee performanceNew!

- Onsite Orientation for Step 2 CS (Video)

Step 3

Practice materials updated November 2020

Download Step 3 tutorial and practice items, including practice CCS cases

- Content Description and General Information Booklet (PDF)

If you have questions or issues, check out the Frequently Asked Questions: Practice Materials. If you do not find the answer you need, please fill out our contact form.

USMLE Computer-based Testing (CBT) Practice Session

Practice Sessions are available, for a fee, for registered examinees who want the opportunity to become familiar with the Prometric test center environment. Register for a CBT Practice Session »

• Watch the instructional video below that illustrates how to run a case using the Primum® software. Then, let us know what you think by taking our brief survey.

• Download the Step 3 tutorial and practice items, which includes practice CCS cases.

• Read the Primum CCS FAQs (PDF) to learn more about the Primum experience.

• Review the links below, which provide feedback on diagnostic and management steps for the sample Step 3 Computer-Based Case Simulations. These also appear at the end of the practice cases.

The CCS database contains thousands of possible tests and treatments. Therefore, it is not feasible to list every action that might affect an examinee's score. The descriptions are meant to serve as examples of actions that would add to, subtract from, or have no effect on an examinee's score for each case.

Case 1: Feedback on a 65-year-old man presenting with acute chest pain and respiratory distress (10-minute case)

Orientation Feedback for Tension Pneumothorax

In evaluating case performance, the domains of diagnosis (including physical examination and appropriate diagnostic tests), therapy, monitoring, timing, sequencing, and location are considered.

In this case, a 65-year-old man is brought to the emergency department by ambulance because of acute chest pain and respiratory distress. Initially the presentation and reason for visit suggest a broad differential diagnosis, but the limited available history narrows the differential. The patient had an acute onset of right-sided chest pain 10 minutes before the ambulance arrived. He rates the pain as an 8 on a 10-point scale. The pain is excruciating, sharp, and increases with respiration.

The patient appears pale and in marked respiratory distress. He is moaning and holding his hands over the right side of his chest. Vital signs show tachypnea, tachycardia, and low blood pressure. Physical examination shows no breath sounds; there is tracheal deviation, jugular venous distention, hyperresonance to percussion on the right side of the chest, faint heart sounds, and weak peripheral pulses. The skin is pale, cool, and diaphoretic. The remainder of the physical examination is unremarkable. The patient's illness, at this point, seems most consistent with an intrathoracic process.

The computer-based case simulation database contains thousands of possible tests and treatments. Therefore, it is not feasible to list every action that might affect an examinee's score. The following descriptions are meant to serve as examples of actions that would add to, subtract from, or have no effect on an examinee's score for this case.

Timely diagnosis and management are essential in this case. An optimal, efficient diagnostic approach would include quickly performing a targeted physical examination that includes chest/lung and cardiovascular examination, cardiac monitoring, and assessing oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry. Treatment should be initiated immediately before the patient’s condition worsens. Ordering anything that might delay treatment (eg, a 12 lead ECG, arterial blood gases, or a portable chest x-ray) would be suboptimal in this case if ordered before the patient’s condition is stabilized.

As soon as the absent breath sounds and exam findings consistent with tension pneumothorax are discovered, optimal treatment would include performing a needle thoracostomy for decompression followed by a chest tube insertion for lung reexpansion. A chest x-ray should be ordered to confirm appropriate tube placement and lung reexpansion. The patient’s blood pressure and respiratory rate should be closely monitored until the patient’s condition has stabilized.

Examples of additional tests, treatments, or actions that could be ordered but would be neither useful nor harmful to the patient include:

- Bronchodilators

- Complete blood count

- Electrolytes

- Analgesics

- Intravenous fluids

Examples of suboptimal or poor management would include failure to examine the chest, admission before treatment, failure to order a chest x-ray after inserting the chest tube and/or needle thoracostomy, delay in treatment to reexpand the lung, or absence of treatment.

In this acute presentation, timing is critically important. An optimal approach would include completing the above diagnostic and management actions as quickly as possible. Delaying diagnosis or treatment and pursuing alternative diagnoses with tests such as a lung scan will waste valuable time and could be harmful or even fatal to the patient. Other examples of treatments that would waste time, subject the patient to unnecessary discomfort or risk, and add no real benefit to this patient include:

- CT before lung reexpansion

- Intubation

- Pulmonary function testing

- Thrombolytic therapy

Case 2: Feedback on a 32-year-old woman presenting with knee pain and swelling (20-minute case)

Orientation Feedback for Rheumatoid Arthritis

In evaluating case performance, the domains of diagnosis (including physical examination and appropriate diagnostic tests), therapy, monitoring, timing, sequencing, and location are considered.

In this case, a 32-year-old woman comes to the office because of knee pain and swelling. From the chief complaint, the differential diagnosis is broad. It includes osteoarthritis, infectious arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), gout, and psoriatic arthritis. The comprehensive history, however, narrows the differential. The patient has experienced increasing fatigue and generalized weakness during the past 4 months. She developed generalized aches and morning joint stiffness during the past 8 weeks and, more recently, pain and intermittent swelling of both wrists, and of the proximal metacarpophalangeal joints, as well as bilateral knee swelling. These signs and symptoms are highly suggestive of a chronic systemic inflammatory process.

Physical examination shows bilateral swollen, warm, and tender wrist, proximal metacarpophalangeal, and knee joints, and bilateral knee effusions. Other physical findings are unremarkable. In the absence of other findings, the patient’s illness, at this point, seems most consistent with rheumatoid arthritis. While the presence of certain clinical features is helpful in excluding other connective tissue diseases and osteoarthritis, further diagnostic evaluation is appropriate to confirm the presumptive diagnosis and establish the severity of the disease.

The computer-based case simulation database contains thousands of possible tests and treatments. Therefore, it is not feasible to list every action that might affect an examinee's score. The following descriptions are meant to serve as examples of actions that would add to, subtract from, or have no effect on an examinee's score for this case.

An optimal, efficient approach to diagnosis would include performing an appropriate physical examination (including extremities/spine, chest/lung, cardiovascular, abdominal, skin, HEENT/neck, and lymph node examinations). A rheumatoid factor test or a cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody (Anti-CCP) test would support the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. The diagnostic workup would also include a complete blood count, arthrocentesis with relevant synovial fluid studies (cell count, crystals, and bacterial culture), an antinuclear antibody assay, and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein test. These tests serve to assess the severity of the disease and consider the likelihood of SLE, gout, an infectious process, or reactive arthritis. In addition, joint x-rays would provide a baseline assessment.

In adult patients, an optimal approach to treatment would focus on relieving pain, decreasing inflammation, preventing or slowing joint damage, and improving function. It is important to manage the acute phase of the disease and to address the long-term care of the patient in this case. Optimal treatment would include a combination of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) or corticosteroid with a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) for comprehensive therapeutic treatment. Administration of a DMARD, eg, methotrexate or etanercept, prevents or slows joint damage, and improves joint function. An NSAID or corticosteroid relieves pain and decreases inflammation essential to provide interim symptom relief while the selected DMARD takes effect. To prevent deformity and loss of joint function, the patient would be advised to exercise appropriately. Or, a referral would be made for physical or occupational therapy.

In this case simulation, when NSAID or corticosteroid treatment is initiated, the patient regularly reports both joint and systemic improvements. Therefore, ordering a rheumatology consult or additional monitoring is appropriate but optional during the time frame of this simulation.

Examples of additional tests and treatments that could be ordered but would be neither useful nor harmful to the patient include:

- Chlamydia trachomatis tests

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae tests

- Antibody, anti-single-stranded DNA

- Thyroid studies

- Urinalysis

- Uric acid, serum

Examples of suboptimal management of this case would include delay in diagnosis or treatment, or treatment with NSAIDS or corticosteroids alone. Treatment with salicylates would also be considered suboptimal management in this case. Although they would temporarily relieve pain when administered in high doses, there are other agents with fewer adverse effects that would be better treatment options. Examples of poor management would include failure to order any physical examination or failure to treat rheumatoid arthritis. With the availability of effective treatment for rheumatoid arthritis and concerns about opioid addiction, narcotic analgesics should have a limited role in treatment.

Examples of invasive tests that would subject the patient to unnecessary discomfort or risk and add no useful information include:

- Arthroscopy

- Synovial biopsy

While many case scenarios run for a relatively short period of simulated time, a matter of hours or days, this scenario runs for a longer period of time, weeks. This illustrates the importance of allowing sufficient time for the patient to respond to treatment and emphasizes monitoring and long-term management.

Case 3: Feedback on a 65-year-old woman presenting with chest pain (20-minute case)

Orientation Feedback for Ascending Aortic Dissection

In evaluating case performance, the domains of diagnosis (including physical examination and appropriate diagnostic tests), therapy, monitoring, timing, sequencing, and location are considered.

In this case, a 65-year-old woman comes to the emergency department because of chest pain. From the chief complaint, the differential diagnosis is broad; however, the comprehensive history narrows the differential. The patient is experiencing sharp, left-sided chest pain that radiates to her left jaw and to her back. The pain began abruptly 45 minutes before the patient came to the emergency department. She is now short of breath and mildly nauseated. She has a history of hypertension for the past 5 years that is being appropriately treated with medication. There is no history of any previous episodes of chest pain either at rest or on exertion. The absence of fever, chills, cough, or pleural rub suggests that the problem is not an infectious pulmonary process.

Physical examination shows hypertension and tachycardia with bounding central and peripheral pulses. The patient is anxious, diaphoretic, and in severe distress from chest pain. Cardiovascular examination reveals a prominent and sustained apical impulse, and an indistinct S2 with S4 audible at the apex, and a grade 2/6 diastolic decrescendo murmur heard best at the right sternal border. HEENT/neck examination shows grade II arteriovenous nicking on funduscopic examination. The remainder of the physical examination is unremarkable. The patient’s illness, at this point, would seem most consistent with a coronary or aortic abnormality with associated aortic regurgitation. In this case, the sudden onset of radiating chest pain along with the bounding pulses, widened pulse pressure, aortic murmur, and long history of hypertension are highly suggestive of the diagnosis of ascending aortic dissection.

The computer-based case simulation database contains thousands of possible tests and treatments. Therefore, it is not feasible to list every action that might affect an examinee's score. The following descriptions are meant to serve as examples of actions that would add to, subtract from, or have no effect on an examinee's score for this case.

An optimal, efficient approach would include performing a targeted physical examination (including cardiovascular, chest/lung, and neurologic/psychiatric examinations), ordering a 12 lead electrocardiography (ECG), and a portable chest x-ray. Optimal medical therapy would include stabilizing the patient with intravenous (IV) medications to lower both blood pressure and heart rate. Suboptimal treatment would include other antihypertensive agents. Lastly, IV narcotic analgesic administration to alleviate pain is important.

The patient's cardiovascular status should be monitored with a cardiac monitor or by ordering repeat vital signs. Some measure of oxygen saturation is also indicated.

Once stable, some form of chest imaging that would assess for an aortic dissection (including computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast, cardiac computed tomography angiography (CTA) with contrast, echocardiography, transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the chest, or cardiac MRI with gadolinium) is needed. The diagnostic workup should also include blood tests for serum creatinine (basic metabolic profile or complete metabolic profile) to assess kidney function, electrolytes to check sodium and potassium concentrations, a complete blood count (CBC) to look for signs of anemia, serum creatine kinase or serum troponin I (cardiac enzymes) to rule out myocardial compromise, and a blood group and crossmatch.

Once the ascending aortic dissection is discovered and aortic root involvement confirmed, optimal treatment should include open heart surgery, endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR), thoracotomy or cardiothoracic surgery, or general surgery consult.

Step 3 Usmle Practice Questions

In this acute presentation, timing is critically important. An optimal approach would include completing the above diagnostic and management actions as quickly as possible (ie, during the first 2 hours of simulated time).

Examples of additional tests, treatments, or actions that could be ordered but would be neither useful nor harmful to the patient include:

- Admitting the patient to the inpatient ward or intensive care unit

- Antibiotics

Suboptimal management of this case would include ordering additional physical examination components that would add no relevant information, administering an IV antihypertensive without a beta blocker, neglecting to order indicated blood tests, or a delay in diagnosis or treatment. It would be suboptimal to order anything unnecessary that would waste time, even if the test or procedure were not invasive or risky (eg, lung scan).

Examples of poor management would include failure to order any physical examination, failure to order an imaging study that would reveal the dissection, failure to administer an antihypertensive agent, or failure to order surgical intervention.

Examples of invasive and noninvasive actions that would subject the patient to unnecessary discomfort or risk include:

- Changing the location to the outpatient office or sending the patient home

- Chest tube

- Exercise ECG

- Heparin

- Laparotomy

- Needle thoracostomy

- Stress echocardiography

- Thrombolytics

- Warfarin

Case 4: Feedback on a 4-year-old boy presenting with shortness of breath (20-minute case)

Orientation Feedback for Asthma

In evaluating case performance, the domains of diagnosis (including physical examination and appropriate diagnostic tests), therapy, monitoring, timing, sequencing, and location are considered.

In this case, a 4-year-old boy is brought to the office because of increasing shortness of breath during the past 3 days. From the chief complaint, the differential diagnosis is broad; however, the comprehensive history narrows it. The patient has been wheezing and has a cough that has been worsening. The mother says that the wheezing seems to get worse after the patient plays outside but resolves shortly after he comes inside. The patient has a history of frequent episodes of “wheezy bronchitis” and ear infections. When the patient was 2 years old, he was hospitalized for 1 week for similar symptoms and treated with intravenous antibiotics and oxygen. At age 18 months, the patient had pressure equalizing tubes inserted. The patient also has a history of allergy to pollen and atopic dermatitis.

Physical examination shows slight tachycardia. Chest/lung examination reveals bilateral, mild, intercostal retractions, and bilateral expiratory wheezes with prolonged expiratory phase, and no crackles. HEENT/neck examination shows pale, boggy, edematous nasal mucosa without nasal flaring. Skin examination reveals dry, scaly patches in the antecubital areas. The remainder of the physical examination is unremarkable. The patient's illness, at this point, would seem most consistent with an obstructive pulmonary disease process. In this case, the increased coughing and wheezing, as well as the history of frequent respiratory and ear infections, are highly suggestive of the diagnosis of asthma.

The computer-based case simulation database contains thousands of possible tests and treatments. Therefore, it is not feasible to list every action that might affect an examinee's score. The following descriptions are meant to serve as examples of actions that would add to, subtract from, or have no effect on an examinee's score for this case.

An optimal, efficient approach would include performing a targeted physical examination (including HEENT/neck, chest/lung, cardiovascular, and abdominal examinations) and addressing oxygen status by ordering pulse oximetry or oxygen therapy. Treating the patient’s respiratory distress with optimal inhalation bronchodilators (such as albuterol or levalbuterol), as well as optimal oral (PO) steroids, is essential.

Optimal management should also include counseling the patient/family about asthma care and the side effects of medication. Monitoring the patient’s respiratory status by ordering a chest/lung examination after treatment is also important.

In this acute presentation, timing is important. An optimal approach would include completing the above diagnostic and management actions as quickly as possible (ie, during the first few hours of simulated time).

Examples of additional tests, treatments, or actions that could be ordered but would be neither useful nor harmful to the patient include:

- Antihistamines

- Antitussives or expectorants

- Pulmonary function tests

- Vaccines

Suboptimal management of this case would include administering a bronchodilator by a suboptimal route (such as intramuscular or oral); or administering a suboptimal bronchodilator (such as atropine or aminophylline); monitoring the patient by ordering arterial blood gas analysis instead of a chest/lung examination after treatment; failing to counsel the patient/family; or a delay in diagnosis or treatment.

Examples of poor management would include failure to order a physical examination, failure to administer a bronchodilator, and failure to address the patient’s oxygen status.

Examples of invasive and noninvasive actions that would subject the patient to unnecessary discomfort or risk, or would add no useful information to that available through safer or less invasive means, include:

- Antibiotics

- Bronchoscopy

- Chest CT

- Endotracheal intubation

- Intravenous sympathomimetics

Case 5: Feedback on a 31-year-old woman presenting with lethargy, nausea, and vomiting (20-minute case)

Orientation Feedback for Diabetes with ketoacidosis; E. coli sepsis

In evaluating case performance, the domains of diagnosis (including physical examination and appropriate diagnostic tests), therapy, monitoring, timing, sequencing, and location are considered.

In this case, a 31-year-old woman is brought to the emergency department by her roommate because of lethargy, nausea, and vomiting. From the chief complaints, the differential diagnosis is broad and includes the many causes of acutely altered mental status. However, the comprehensive history narrows the possible differential diagnoses, making uncontrolled diabetes very likely. The patient has been experiencing nausea and vomiting for the past 24 hours and has been unable to eat during that time. During the past hour, she has become drowsy and lethargic. She has a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus, for which she normally takes insulin multiple times daily. However, she has had no insulin during the past 24 hours. The patient’s roommate says that the patient experienced some chills yesterday.

The patient appears drowsy, lethargic, and acutely ill. Physical examination reveals elevated temperature, tachypnea, tachycardia, and hypotension. Cardiovascular examination shows thready central and peripheral pulses. Skin examination reveals poor turgor. HEENT/neck examination shows dry mucous membranes. Abdominal examination reveals diffuse mild tenderness without guarding, rebound, or masses. Neurologic/psychiatric examination shows that the patient is lethargic but oriented. Taken together, the history and physical examination findings support the initial impression of complications of type 1 diabetes mellitus. In this particular patient, the history of type 1 diabetes mellitus presenting with prolonged nausea and vomiting and lethargy and drowsiness, combined with the physical examination findings of fever, thready pulses, tachycardia, signs of dehydration, and diffuse abdominal tenderness are highly suggestive of the diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis due to infection and inadequate insulin.

The computer-based case simulation database contains thousands of possible tests and treatments. Therefore, it is not feasible to list every action that might affect an examinee's score. The following descriptions are meant to serve as examples of actions that would add to, subtract from, or have no effect on an examinee's score for this case.

Usmle Step 3 Practice Test

An optimal, efficient approach would include performing a targeted physical examination (including chest/lung, cardiovascular, abdominal, and neurologic/psychiatric examinations), and ordering a serum glucose test using a glucometer and a urinalysis or complete blood count (CBC) to check for signs of infection. Stabilizing the patient with optimal intravenous (IV) fluids (eg, Lactated Ringer solution or normal saline solution) to improve hydration, and treating the patient empirically with a broad-spectrum IV or intramuscular (IM) antibiotic to cover the most likely sources of infection are important. Once the serum glucose result is obtained, starting IV insulin to treat the hyperglycemia is critical. The patient’s cardiovascular status should be monitored by ordering repeat vital signs or by changing the patient’s location to the inpatient unit or intensive care unit.

The diagnostic workup should also include arterial blood gas analysis to assess acidosis, bacterial blood culture to identify the organism before administering empiric antibiotics, and serum electrolyte measurements (ie, potassium) to assess the severity of dehydration. Serum creatinine or urea nitrogen measurements (basic metabolic profile or complete metabolic profile) to assess kidney function are indicated. Continued monitoring of the patient’s serum glucose, electrolytes, particularly potassium, and arterial blood pH after treatment is also important.

In this acute presentation, timing is critically important. An optimal approach would include completing the above diagnostic and management actions as quickly as possible (ie, during the first hour of simulated time).

Examples of additional tests, treatments, or actions that could be ordered but would be neither useful nor harmful to the patient include:

- Antiemetics

- Proton pump inhibitors

- Lumbar puncture

- Abdominal imaging

- Antipyretics

- Oxygen

- 12-lead or rhythm electrocardiography

Suboptimal management of this case would include delay in diagnosis or treatment; administering suboptimal IV fluids (eg, hypotonic saline solutions, dextrose in water, or dextrose in Lactated Ringer solution); initial treatment with subcutaneous insulin; suboptimal IV or IM antibiotics; or neglecting to order indicated blood tests. It would be suboptimal to order unnecessary tests or procedures that would serve no clear diagnostic or therapeutic purpose even if those actions are low-risk.

Examples of poor management would include failure to order any physical examination; failure to order a serum glucose test; failure to order a blood culture to determine the cause of the infection or failure to order a blood culture before administering empiric antibiotics; failure to treat with IV fluids, antibiotics, and insulin; or failure to monitor the patient after treatment.

Examples of invasive and noninvasive actions that would subject the patient to unnecessary discomfort or risk or would add no useful information to that available through safer or less invasive means include:

- Gastric lavage

- Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

Case 6: Feedback on a 25-year-old pregnant woman presenting with a seizure and loss of consciousness (10-minute case)

Orientation Feedback for Eclampsia

In evaluating case performance, the domains of diagnosis (including physical examination and appropriate diagnostic tests), therapy, monitoring, timing, sequencing, and location are considered.

In this case, a 25-year-old woman at 38 weeks’ gestation comes to the emergency department after suffering a seizure with loss of consciousness about 10 minutes earlier. From the chief complaint, the differential diagnosis is broad; however, the comprehensive history narrows it. The patient is gravida 1, para 0, and has been receiving routine prenatal care. The pregnancy has been uncomplicated so far. She has had a severe headache for the past 3 days, and her feet have appeared swollen during the past 2 to 3 weeks. She has no previous history of seizures, and there is no history of hypertension or renal or neurologic disease. The patient is conscious but appears confused.

Physical examination shows tachycardia, a low-grade fever, and elevated blood pressure. Cardiovascular examination shows a loud S4 and bounding central and peripheral pulses. There is a grade 2/6 systolic ejection murmur at the left sternal border without radiation. There is marked vasospasm on funduscopic examination with normal disc margins and a minor tongue laceration. Abdominal examination shows a gravid uterus with a fundal height of 37 cm. Estimated fetal weight is 2700 g (6 lb). The fetus is cephalic by palpation with a fetal heart rate of 144 beats/min. Genital examination reveals an edematous vulva. The cervix is dilated to 1 cm and 50% effaced. Extremities/spine examination shows 4+ pitting edema in both lower extremities to the midthigh region. Neurologic/psychiatric examination shows that the patient is conscious but oriented to person and place only. Deep tendon reflexes are 4+ with bilateral clonus at the ankles. The remainder of the physical examination is unremarkable. The patient's illness, at this point, would seem most consistent with a neurologic or cardiovascular abnormality, possibly pregnancy-associated. In this pregnant patient, the new onset of seizure, elevated blood pressure, lower extremity edema, and hyperactive reflexes are highly suggestive of the diagnosis of eclampsia.

The computer-based case simulation database contains thousands of possible tests and treatments. Therefore, it is not feasible to list every action that might affect an examinee's score. The following descriptions are meant to serve as examples of actions that would add to, subtract from, or have no effect on an examinee's score for this case.

An optimal, efficient approach would include performing a targeted physical examination (including skin, HEENT/neck, chest/lung, cardiovascular, abdominal, genital, extremities, and neurologic/psychologic examinations) and ordering a complete blood count (CBC) to rule out hemolysis. Stabilizing the patient with intravenous (IV) magnesium sulfate to prevent another seizure, plus an IV optimal antihypertensive (hydralazine or beta blockers) to reduce blood pressure, is important. Once the patient’s condition is stabilized, it is imperative to deliver the fetus either by stimulating contractions using optimal uterotonics, by performing a cesarean delivery, or by consulting obstetrics/gynecology. The fetal heart rate should be watched until delivery by ordering a fetal monitor. Some measure of the patient’s urine output is also indicated.

The diagnostic workup should also include a urinalysis and blood tests for the following: serum creatinine or urea nitrogen (basic metabolic profile or comprehensive metabolic profile) to assess kidney function; electrolytes to check sodium and potassium levels; liver enzymes; and platelet count to diagnose HELLP syndrome.

In this acute presentation, timing is critically important. An optimal approach would include completing the above diagnostic and management actions as quickly as possible (ie, during the first hour of simulated time).

Examples of additional tests, treatments, or actions that could be ordered but would be neither useful nor harmful to the patient include:

- Arterial blood gases or Pulse oximetry

- Fibrin breakdown products

- Thrombin time, plasma

Examples of poor management would include failure to order a neurologic/psychiatric examination, failure to administer an antihypertensive agent, failure to monitor the fetus or mother, or administering a suboptimal seizure medication (phenobarbital).

Examples of invasive and noninvasive actions that would subject the patient to unnecessary discomfort or risk, or would add no useful information to that available through safer or less invasive means, include:

- Changing the location to the outpatient office or sending the patient home

- Mifepristone PO

- CT, abdomen/pelvis

- Carboprost IM

- Alprostadil IV

- Dilatation and curettage

Copyright Information

The United States Medical Licensing Examination is a joint program of the Federation of State Medical Boards of the United States, Inc. and the National Board of Medical Examiners. The practice package includes proprietary information and materials that are licensed by the National Board of Medical Examiners or owned and copyrighted by the Federation of State Medical Boards and the National Board of Medical Examiners.

As to the materials that are owned and copyrighted by the NBME and FSMB: Copyright © 1998- the Federation of State Medical Boards of the United States, Inc. and the National Board of Medical Examiners, except for the following: Copyright © 2016- National Board of Medical Examiners as to the computer program test driver. Primum® Computer-based Case Simulation Software Version 8.3, Copyright © 2009- the National Board of Medical Examiners. Runtime library portions of the software included with permission from Versant Corporation, Copyright © 1996. All rights reserved. Portions of Step 2 CS practice materials reproduced with permission from the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG®) Clinical Skills Assessment (CSA®) Candidate Orientation Manual, Copyright © 2002 by the ECFMG. Microsoft® PowerPoint® Viewer, included in this software, is a product of Microsoft® Corporation. Permission to use this software and the other materials installed with it is limited to exam preparation or practice by individuals who are registered to take the examinations, and further reproduction, distribution, transmission, or other uses are prohibited without permission from the copyright holders.

- Requirements

- Windows operating system

- Administrative rights - Control Panel > User Accounts > Change account type

- Chrome set as default browser (Free download available)

- WINZIP (Free download available)

- Computer settings

- Control Panel > Appearance and Personalization > Display = 100%

- Control Panel > Appearance and Personalization > Display > Resolution

- Windows 7, at least 1024 x 768

- Windows 10, at least 1280 x 800

- Control Panel > Clock, Language, Region > Region and Location >

- Formats = English (United States)

- Location = United States

- Keyboard & Language > Change Keyboards > General = English (United States) - US

- Administrative > Current Language = English (United States)

- File sharing software must be disabled (e.g., uTorrent, drop box, google drive)

- Pop-up blocker must be disabled

- Double click on downloaded file to extract installation file

- Double click on installation file and follow prompts

- Double click on program to run

- Troubleshooting

- If you receive an error during download or installation, please double check all steps under # 1 and 2 above.

- You must uninstall all previous copies of the application before attempting to download and reinstall.

If you still experience issues after following the instructions above, please contact us.